Image by Melissa Ballesteros / CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

A script might be the heart of every film, but another part of the production process that is just as influential is the storyboard. During the early stages of production, artists outline a narrative structure with storyboards, which are sketches or images that represent the shots in a film, breaking down the main plot and order of events. Storyboards are a useful part of the pre-visualization stage, making the concept of a film less of an abstraction.

Storyboards: Roadmap to a Film

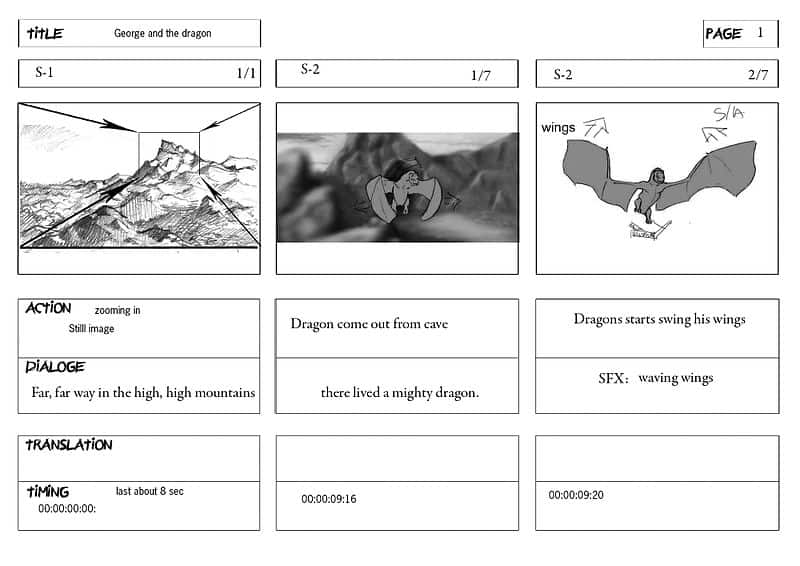

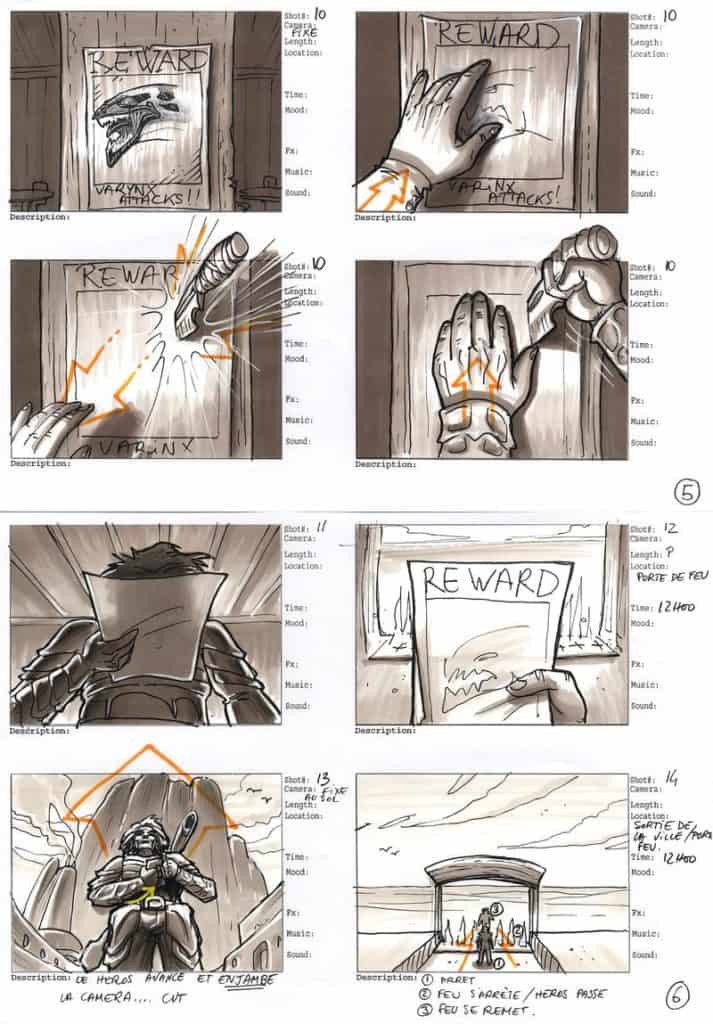

Storyboards are crucial because it serves as a visual roadmap for the duration of a film’s development.They’re often in the form of pencil drawings or digital illustrations, usually with minimal color or grayscale to indicate shadows and contrast. Production and development crews can refer to storyboards to convey plot ideas, character actions, establish scenes, and other aspects of visual storytelling. They can also be used to pitch movie concepts to studios, who usually decide to greenlight production based on a successful and persuasive storyboard pitch.

Because of their flexibility and lack of detail, artists can use them as a blueprint to suggest the final look of a film, as well as adapt ideas concepts and sequences as needed. By the end of a presentation, a great storyboard should hook its audience and sell the essence of a movie or interactive medium.

A storyboard is essentially an illustrative outline of the film’s cinematography. Remember that you don’t need to have great drawing skills to make one! When envisioning a storyboard, artists should illustrate from the director or cinematographer’s point of view.

Elements of a Storyboard

Each shot of a storyboard captures several key elements: subject, background, camera shot, and the camera’s movement. Within a shot is the subject, the central character or object of a frame, and the foreground and background of a shot. Some key terms for a storyboard include:

- Shot – Titled with scene # and shot # ie Shot 1.4. Shot types include establishing close-up, POV, dolly shot, wide shot, full shot, etc. You can learn more about different shots here.

- Panel – Conveys a shot’s aspect ratio. Common aspect ratios are 16:9, 2.39:1, and IMAX

- Sequence – Consists of multiple shots. A sequence of shots represent a scene in a film. Each sequence comes with its own Title.

- Description – Storyboard artists or directors can add more details about a scene, as well as instructions for how the camera operator should capture shots

- Arrows – Arrows indicate the direction the camera moves (pan, in, out, etc.)

Below the panel artists can write more details or instructions related to the scene. Arrows are also used to establish camera movement, which can be seen in the following storyboard.

Stitching a Cohesive Narrative

Sketching out a storyboard is an opportunity to develop story ideas, but don’t stray too far from key scenes by adding too many details and convoluting the story. To stick to major plot points, it helps to create a script beforehand is helpful so you have a reference for the sequence of events. At this early stage, it’s adequate to show the most significant parts so don’t be tempted to create filler shots. Make sure your storyboard stays concise by using these strategies:

- Only move the camera with purpose

Your natural instinct is to move the camera as often as you can, but it’s easy to overdo it. All your camera movements need to have intent, whether you’re switching angles or cutting to the next scene. Step back and ask yourself if switching to a different a certain angle enhances a scene or provides narrative context. Be careful not to have too many still moments in succession by varying your shots to create a sense of movement and action.

Move the camera to assert location, position of characters so that the audience is always able to follow the scene structure. The last thing you want to do is leave the viewer wondering what’s going on and ultimately detached from the film.

- Use lines to create depth and dimension

Since you’re drawing 2 dimensional illustrations for a 3 dimensional scene, pay careful attention to lines, both drawn and imaginary. Creating a sense of depth should be one of your primary goals. Mix up different types of shots, such as one focusing on the foreground and ones that feature the background.

Imaginary lines called axis lines help artists establish focal points within a scene. Be mindful of where the axis lines are positioned or converge to avoid conflicts in composition. A common rule of thumb is that the axis line should never be crossed. The camera should always be facing one side of the axis lines in each scene to avoid confusing the audience.

Mistakes To Avoid

Artists can run into amateur mistakes when they create their storyboards. Watch out for these common errors:

- Odd Camera Angles

Before you sketch a scene, consider the possible camera perspectives and avoid awkward angles. You want to draw shots not just from a human perspective, but shots that frame the scene in a natural way. Going for stylish, cinematic is encouraged, though don’t overdo it by opting for experimental shots that don’t add to the narrative you’re trying to tell. Try not to draw from diagonal angles or angles that are positioned directly up or down.

- Messy Composition

Sloppy composition never looks good, no matter how you try to present it. This one should be a no-brainer, but it’s easy to ruin a great composition with a lack of attention to detail. Each sketch should be aesthetically pleasing on its own. There should be a balance that should translate well on screen.

- Poor Scene Transitions

While messy compositions is about containing the elements inside of a frame, the same organization should be applied when you’re switching to another scene. Transitions, or cuts, should be smooth and should never be abrupt or jarring. Scenes need to have a beginning, middle, and end before moving on to the next scene.

Wrapping It Up

A storyboard allows artists to experiment with open interpretations of a film; it’s a true test of visual storytelling, with numerous directions you can take the story in. Not every idea will translate well from panel to screen, but part of the fun of a storyboard is how each detail isn’t set in stone. Drawing professional quality storyboards will help you hone your skills in refining a film’s storytelling and aesthetic, bringing your imagining much closer to reality.

Learn more about storytelling techniques in our new course Cinematic Storytelling from California College of the Arts taught by Craig Good, who holds 30 years of experience in animation. Enroll for free below:

Cinematic Storytelling

California College of the Arts